Also this issue: Allah Behind Bars Putting the Fish Behind You Miracle on Market Street The Bell Curve |

|||||||||

November 7-13, 2002

city beat

Repeat Offender?

|

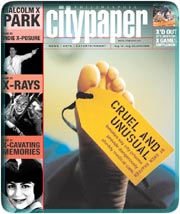

Despite complaints, the city has rehired Prison Health Services to run its inmate health care.

In early October, the city of Philadelphia awarded a new $36 million contract for health care in its jails to the very same firm it booted in June. Now some industry players are questioning the circumstances under which the deal was signed.

Philadelphia Managing Director Estelle Richman originally announced plans to terminate its contract with Prison Health Services (PHS) in late June. That decision followed a yearlong campaign by health care advocates, who accused the company of grossly neglecting the medical needs of inmates. They have been slamming PHS for a number of questionable deaths in city jails, overuse of psychotropic drugs and severe staff shortages. PHS officials declared the company was anxious to escape from Philly's jails, as the company was bleeding money on the $25 million contract it negotiated in 2000.

PHS lost $1.7 million during fiscal year '01 and $4.6 million during fiscal year '02, according to City Council testimony given Oct. 8 by Timothy Gill, deputy managing director for the city. Even so, PHS agreed to stick around for three months after its contract expired -- in exchange for $9.1 million -- while the city sought a replacement.

In July, a freshly drafted Request for Proposal (RFP) was published. It included a number of changes in the "scope of services" that bidders were expected to provide. Two companies, Wexford and Correctional Medical Services (CMS), submitted bids ranging from $39.5 million to $41 million annually. A PHS official attended the pre-bid conference, but the company ultimately opted not to play.

Imagine the surprise, then, when the city announced in early October that PHS' contract was being extended for about $36 million annually. On top of this base compensation, the city is sharing the hefty price tag of malpractice insurance; hospital specialty care; and "ancillary costs" such as pharmacy expenses, lab testing for hepatitis C and salaries for various staff positions.

In an Oct. 10 letter to City Councilman Angel Ortiz, a CMS official questions whether the RFP process was merely a "charade" to "maintain the status quo" while increasing PHS' contract by at least 28 percent.

"We've never been treated so non-professionally," says Gary McWilliams, vice president of sales and marketing for CMS. "We flew eight people to Philadelphia on Sept. 5, and spent an entire day discussing the terms of the contract. Etiquette would dictate that they call us and let us know they're giving the contract to someone else. Instead, we learned about it on PHS' website."

Wexford officials say they are feeling similarly burned by the RFP process. After the city told Wexford it had 24 hours to answer about 50 detailed questions, some of them "loaded," the health care provider called off its oral presentation, says Robert Matonte, senior vice president of business development.

"I told Mr. Gill we were not coming to orals the next day because the company would be subjected to a forum where we'd look foolish," Matonte says. "I said we'd be happy to sit down, face to face, with representatives from Philadelphia and discuss the costs and risks -- but we were not going to shoot from the hip at orals."

Gill told Matonte to put his concerns in writing. Wexford never heard from the city again. Matonte says he predicted "early on" that PHS would hold onto its contract in Philadelphia.

"Any procurement process can be manipulated to show officials are following proper procedure, even when the outcome is long pre-determined," he adds.

PHS officials say they were sincere when announcing plans to leave Philadelphia's jails at the end of September. Over the summer, PHS even notified employees of upcoming mass lay-offs, as required by the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act, says PHS spokesperson Colleen Roche.

"There was no shell game here," she says. "We'd started the disengagement process."

Gill testified that bids from CMS and Wexford were rejected because they were "significantly higher" than $36 million, as well as because they included "quite a bit of exceptions from the RFP." Frank Keel, spokesperson for Mayor Street, says he is "surprised" that Wexford and CMS officials harbor animosity over the RFP process.

"The city made a concerted effort to find responsible bidders," he says. "These two firms came in at eye-poppingly high levels, without bringing any more to the table. We finally determined it was in the city's best interest to continue our relationship with PHS."

Given that this fall marked Wexford's third attempt to bag a contract in Philadelphia jails, Matonte says he is uncertain whether the company will throw its hat in the ring during the next go-around.

"We'd have a problem assessing whether the city sincerely wants to change vendors," he says. "The city dangles this carrot -- that it's not happy with PHS -- then it's business as usual. Still, we can't afford not to bid on a big piece of business like Philly.... You don't ignore a $40 million project."

And according to McWilliams, PHS' most recent deal with the city may be the sweetest one in the industry. "This new contract has significant protections, more so than any other contract that I'm aware of," he says.

Ortiz, who has sponsored several hearings on correctional health, wants to know if this is true. In an Oct. 16 letter to Richman, Ortiz requests "a complete breakdown of the costs that have been absorbed by the city as a result of the PHS contract."

Prison health advocates have condemned the care PHS provides to inmates. With the company in city jails through at least the end of June 2003, activists are urging Richman to provide vigilant oversight of the contract. Philadelphia should fine PHS if it fails to meet contractual obligations, they say.

"PHS is a for-profit company," points out Rob O'Brien of the Philadelphia County Coalition for Prison Health Care. "It will fix a problem if it's fined."

Ortiz isn't waiting to test this theory, however. He recently introduced legislation that would require City Council to approve contract renewals with vendors -- making it impossible for a city agency to automatically extend major agreements like the one with PHS.